Table of contents

- Intro

- What is patentability and what are the patentability requirements?

- Why is patentability important when considering a patent application?

- Patentability versus non-patentability

- What is meant by a Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art?

Did you know that Halliburton once tried to obtain a patent on the very process of filing a patent?

The US oil giant – once chaired by Dick Cheney – filed the application in 2007 and even listed the ‘filing of claims’ as one of it’s methods along with ‘include attempting to obtain a monetary settlement from the second party based on the assertion of infringement of the claim’.

Needless to say, the application was rejected and later abandoned, no doubt due to its absurdity and the more important factor that it didn’t meet any of the patentability requirements outlined by The USPTO.

In this guide, we explain those requirements for patentability and the considerations of The US patent office and others worldwide.

We have already covered what makes an invention eligible for a patent in “An Inventor’s Guide to Understanding Patent Eligibility“. This article follows on from that, so I highly suggest reading that first.

What is patentability and what are the patentability requirements?

Patentability is essentially the second threshold in the patent process (after eligibility). It is the stage at which your invention or method will undergo intensive scrutiny from the patent examiners to determine whether it is patentable by meeting the patentability requirements that all patent offices observe worldwide. These are:

- Patent novelty.

- Non-obvious.

- Useful.

- Adequately described & properly claimed.

Why is patentability important when considering a patent application?

The likelihood of obtaining a patent without your invention or method ticking all of the boxes above will be slim. Although not impossible, you may be required to prove your claims, which could be easier said than done. There have been few successful cases where a court decision has overturned the patent office’s judgment, and this will add more time and expense to an already lengthy process.

Section 101 of patent law states that: ‘Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefore, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.’

Patentability versus non-patentability

Strong emphasis is placed on these provisions, however, these are broad guidelines and do come with some ambiguity and subjectivity. Therefore, a detailed and well-drafted application along with concise drawings are crucial to the success of your patent being granted.

PATENT NOVELTY

Patent novelty means your invention has to be the first of its kind in the world, or a significant improvement of an existing invention, which greatly enhances it to the benefit of the public and which will not compete with its predecessor.

This requires a patent novelty search to determine whether there are any patents that already cover the invention, anything deemed too similar which could potentially infringe, or any existing prior art published that could invalidate your patent.

NON-OBVIOUSNESS

This category has raised questions in the past and unfortunately isn’t as straightforward as it implies – not an obvious variant of other patents.

So, what constitutes ‘obvious’ and to whom? A new type of battery using a new type of material may be obvious to someone who has spent 20 years working at some of the leading battery manufacturers, to myself or a high-court judge, that wouldn’t be the case.

Patent law stipulates a standard when referring to obviousness and knowledge, which are set using a hypothetical human, known as a ‘Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art’.

Section 102 of patent law provides that “(a) Novelty; Prior Art. — A person shall be entitled to a patent unless;

(1) The claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention; or

(2) The claimed invention was described in a patent issued under section 151, or in an application for patent published or deemed published under section 122(b), in which the patent or application, as the case may be, names another inventor and was effectively filed before the effective filing date of the claimed invention”.

Section 103 states that “A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains. Patentability shall not be negated by the manner in which the invention was made”.

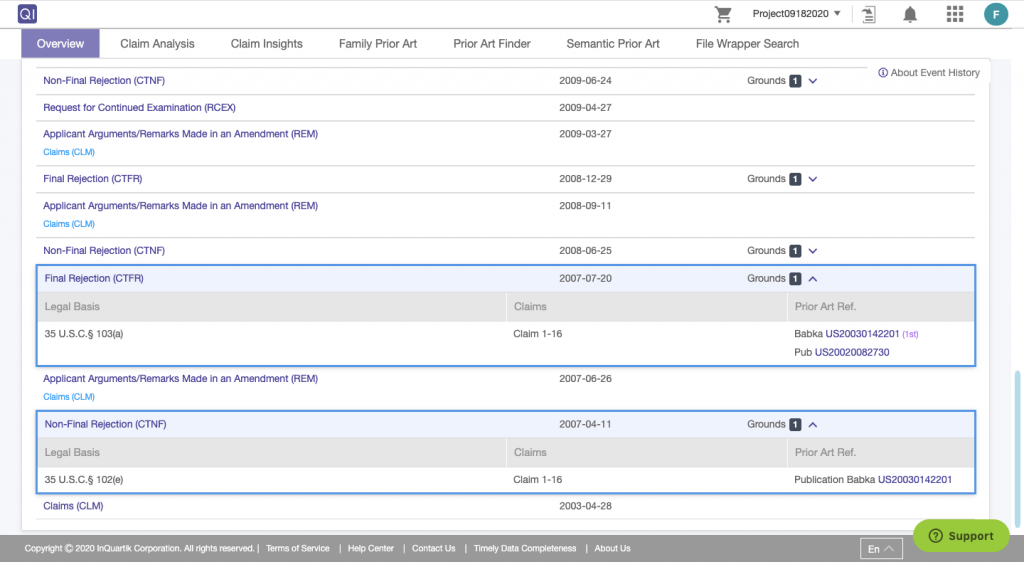

In case number US7777777B2, in which Cisco Technology‘s patent application was rejected multiple times – eventually leading to it being granted several years later – the USPTO found that both section 102 and 103 were relevant in its decision for rejection during the filing and appeal process, because of obviousness and non-disclosure of information.

USEFUL (UTILITY)

This requirement is a fairly low bar, but needs to show that your invention or method:

- Achieves what it was originally set out to do.

- Is feasible in today’s world.

- Is of benefit to people either directly or indirectly.

A patent examiner will evaluate the above criteria and decide whether your invention goes above and beyond to improve that of what currently exists within the market.

ADEQUATELY DESCRIBED & PROPERLY CLAIMED

Commonly debated as the most important part of the patent process – and for good reason.

The importance of the patent description and claims that sit alongside your invention cannot be underestimated.

Both written and illustrated explanatory draughts need to be submitted according to your IP strategy and will most likely entail the right balance of broad and narrow claims. This process should be undertaken by a patent and IP attorney, as this is the reason all litigation cases are won and lost.

Real case — using Quality Insights

Step 1: Sign up for a free, no-obligation account here. (No credit card required).

Step 2: Click on the US7777777B2 or Cisco Technology link above.

Step 3: On the overview page, scroll down to see how the patent was rejected and fought at different stages in the prosecution history.

What is meant by a Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art?

A person having ordinary skill in the art is defined as someone who works in any given industry as a worker with normal and average skills, and who thinks along the line of conventional wisdom in the art. This person is not a genius nor are they someone who undertakes to innovate. They are presumed to be aware of all of the pertinent prior art.

If it would have been obvious for this fictional person to have thought up the invention from the existing prior art, then the creation is deemed not patentable. There have been numerous attempts to question the level of obviousness and knowledge of the person having ordinary skill in the art, and it is a well-considered strategy used by law firms to defend and initiate litigation or appeal against patent rejections.

Did you find this patentability requirements article helpful? Please leave us your comments and feedback over on our LinkedIn and Facebook pages.

You can check out our free Patent Lifecycle Management whitepaper covering everything from preparation to monetization of your patent or use Quality Insights to examine a patent for its §102/§103 issues and more! Start your free trial today!