Patents are valuable assets. They can be bought, sold, and licensed. In this article, we will take a closer look at patent licensing, first with the basics, then patent licensing from a patent owner’s perspective.

Table of contents

- What is Patent Licensing?

- Approaches to Patent Licensing

- Types of Patent Licenses

- How to Find Potential Licensees?

- Why Should or Shouldn’t I License My Patent?

What is Patent Licensing?

When a patent is licensed, an agreement is made between the patent owner (or the licensor) and the person or company that wants to use and benefit from the patent (the licensee).

It permits the licensee to make or sell the product, design, or technology in the patent. The patent then creates income for both the licensee and the licensor through revenue and royalties for the duration of the licensing period.

Arm Ltd., a British CPU developer is an example of a patent licensing powerhouse. Their main business is in developing processors (CPUs) and licensing their patents and technologies to other companies. Currently, ALL of Apple’s devices — such as iPhones and iPads — use Arm chips. Nearly all of Arm’s revenue comes from licensing.

Other examples include the tech giants like IBM and Qualcomm which even have their own licensing programs, inviting businesses to license their patents. Qualcomm, owning over 140,000 patents, has an approximate average of 1 billion dollars in licensing revenue per quarter!

Approaches to Patent Licensing

There are two main approaches to patent licensing — the carrot approach and the stick approach.

Carrot Approach

In this “friendlier” approach, the patent owner (and potential licensor) must persuade the potential licensee to license the patent. In this case, the potential licensee has not infringed the patent at issue, and they can simply refuse to license the patent. So, it is up to the patent owner to convince the potential licensee that the product, design, or technology covered by their patent will benefit the potential licensee in some way, usually by helping them to make money.

Stick Approach

In this more “serious” approach, it has already been determined that the potential licensee has infringed the patent at issue and is using the technology in the patent in some way. The “stick” in this approach is litigation, and the basic message is that the potential licensee must license the patent or face a lawsuit.

As one IP attorney once said, every licensing offer is in fact a potential lawsuit — it’s just that in the carrot approach, litigation is implied, and in the stick approach, it is stated directly. Most often than not, the carrot approach is just a stick approach in disguise.

Types of Patent Licenses

There are basically three types of patent licenses — exclusive, non-exclusive, and partially-exclusive licenses.

- Exclusive Licenses

An exclusive license allows only one licensee to benefit from the licensing agreement. In this type of license, the licensor remains the owner of the patent. It should be noted that some exclusive licenses also include the enforcement rights (all substantial rights) of the patent. Simply stated, the licensee holds all rights to the patent, except for ownership, meaning that the licensee can sue infringers. - Non-Exclusive Licenses

This type of license permits multiple licensees to produce the invention, design, or technology, without any exclusive rights. - Partially Exclusive Licenses

Partially exclusive licenses grant exclusivity to certain applications of a patent, geographic limitations, or a term period. For example, a partially exclusive license for an infrared sensor patent is limited to medical use and cannot be used for military or surveillance applications.

The types of license agreements are not limited to the three listed above. Others may include the co-exclusive license where the licensor only licenses to a limited number of licensees or where licensees must meet certain criteria. Another type of license would be a sole license in which the licensor only licenses a patent to a single licensee but still keeps the rights to exploit the patent. There is even the compulsory license where the patent owner is forced by the government to allow others to use their patent for a set fee, mostly seen in the pharmaceutical industry.

Also, sub-licenses are often mentioned in licensing agreements. The right to sub-license technology to a third party will be stipulated in the original license agreement. Exclusive license agreements are more likely to include sub-licensing rights.

Check out The Story of Intel, Apple, and Qualcomm: The Apple and Qualcomm Lawsuit for a real-life example of licensing involving high-profile companies.

How to Find Potential Licensees?

Before rushing out to find potential licensees to license your patent, you will need to know your patent. Owning a patent does not mean that you are guaranteed to generate revenue from it. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate your patent’s marketability and know your position in the marketplace before any investment is made. To fulfill the goal of licensing a patent profitably, here are a few questions you can ask yourself:

- What is the uniqueness of your patent?

- Does your patent provide an irreplaceable feature to the market?

- What type of licensee may be interested in your patent protection?

After you have confirmed that your patent has licensing potential, the key to generating revenue is to find the right licensees.

To find potential licensees, you should:

First, analyze your patent portfolio. You can first pinpoint the valuable patents in your portfolio and filter out the patents with low quality and value.

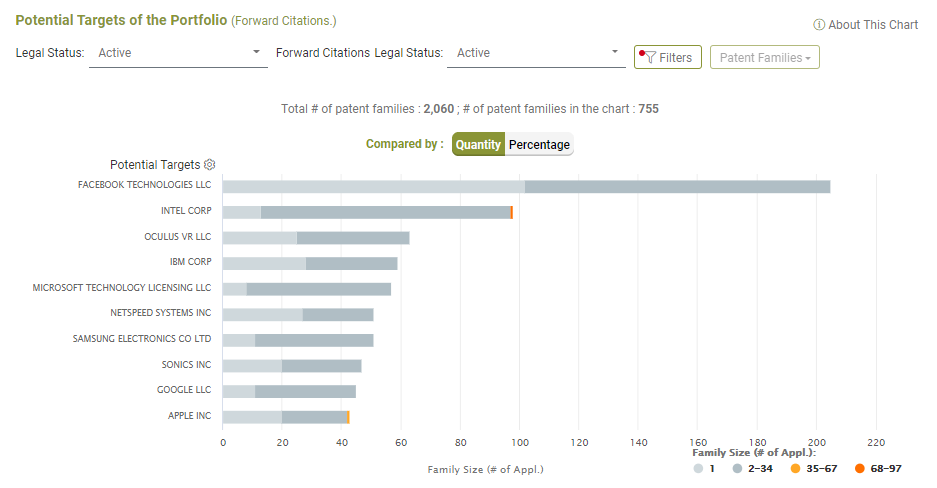

Second, look into the forward citations of your valuable patents. Companies that have cited your patent for reference may be potential targets. One important thing to remember is that you must make sure that your target is practicing in the same country that you have the patent in, if you do not have the authority to practice in that country, you cannot stop others from using the technology.

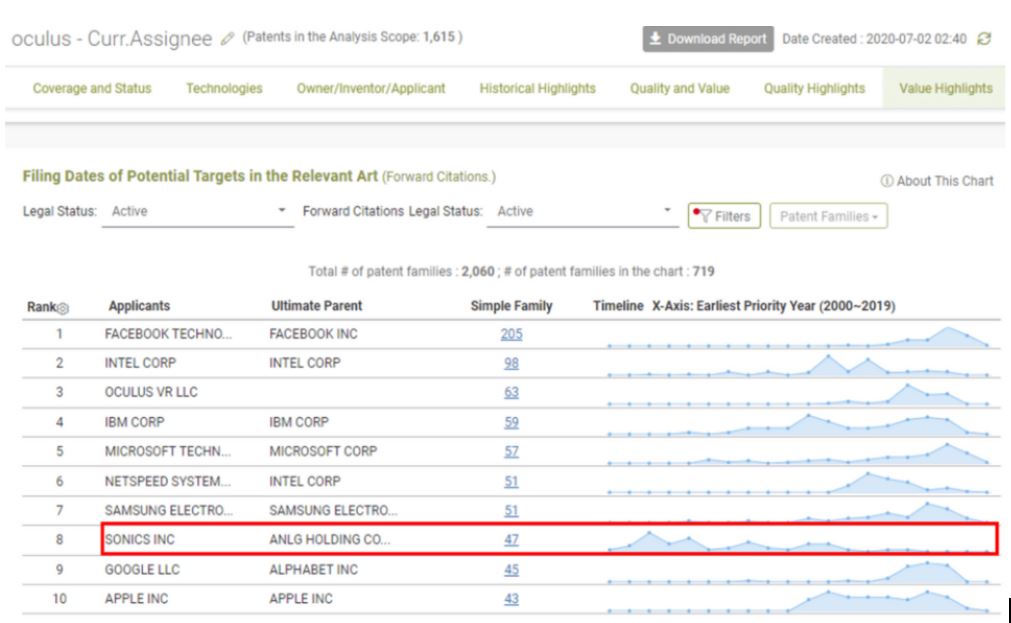

Another point worth noticing is the time frame of the citation. If a company was actively citing your patent, but had not been doing so for an extended period, it is quite possible that that company is no longer leveraging this technology. From the chart below, we can presume that Sonics Inc. is no longer using Oculus’s technology, and Apple has been actively using it in recent years. Therefore, Sonic Inc. might not be a great licensee candidate.

If you have the budget and would like to seek professional assistance, it is always a great idea to enlist the help of a patent brokerage or a patent attorney with experience in patent licensing.

Why Should or Shouldn’t I License My Patent?

Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of licensing your patent.

Why you should:

- Avoid the hassle of running a business

If you are an inventor who enjoys inventing new products, designs, or technology, you may decide to patent your invention but not want to go to all of the trouble of producing, marketing, or selling your product or technology. You can let others take this on and simply enjoy the royalties a licensing agreement can provide. - Reduce investment in commercializing

This is especially true if you lack capital or business experience. You may have the research and development skills, but commercializing takes much capital and many organizational resources. - Enter markets faster

If your licensee is a well-recognized company, your invention will be able to enter the market faster than if you took on commercialization yourself, owing to their experience, infrastructure, reputation, and possible reach into international markets. - Retain your ownership of the patent

Licensing only grants the use of a patent. With ownership, you can enforce your patent by suing infringers.

Why you shouldn’t:

- Hold on to your technology

You may not want to license your patent if the invention, design, or technology covered by the patent is an important part of your business or future business strategy. - Lose autonomy of the invention

If you are relying on the licensee to commercialize your invention, the responsibility of success or failure will be up to the licensee. You could end up failing to make any money if the licensee is unsuccessful in its efforts. - Licensing is not a quick-cash solution

If you think you will get a load of money once a license agreement is completed, think again. Nearly all patent licensing agreements are paid through royalties. The licensee will need at least 6 ~12 months before manufacturing and generating revenue, and this is under the assumption that the licensee is successful. You may receive a signing fee at the start of the agreement, mostly in cash, but sometimes in stock. If you are looking for a larger lump sum, you can consider selling your patent.

Conclusion

Locating potential licensees can be time-consuming, and negotiating the best terms for a patent license is not always easy. This may include requiring the licensee to meet specific milestones and prepare periodic performance reports after licensing, all of which need to be negotiated before signing the agreement. We strongly advised that due diligence be conducted thoroughly.

Maintaining clear channels of communication with the licensee is also important, as disputes may lead to legal fees and hassles in the future.

When it comes down to it, every patent owner’s situation is unique, and the question of whether to license one’s patent to others must be considered carefully.

In the next part of this article, we will delve further into this topic and take a closer look at licensing from a licensee perspective, licensing royalties, and some good-to-know information.

Want to take a look at your patent portfolio and find potential licensing targets?

Contact your Success Client Specialist to experience Patentcloud’s Due Diligence now!

*No credit card required